In an industrial grey warehouse located in Wynwood’s Art District and safely nestled between World Class Boxing -The Scholl Collection and the well known Fredric Snitzer Gallery, we find one of Miami’s most cutting edge-contemporary art spaces, Kevin Bruk Gallery. Since the opening of his first space in the Design District seven years ago, Kevin Bruk has exhibited the works of established contemporary artists like Peter Halley, Kenny Scharf, and Fabian Marcaccio alongside significant emerging ones such as Matthew Brannon, Blake Rayne, and Daniel Hesidence, earning him a reputation of having an “eye for painting”.

In an industrial grey warehouse located in Wynwood’s Art District and safely nestled between World Class Boxing -The Scholl Collection and the well known Fredric Snitzer Gallery, we find one of Miami’s most cutting edge-contemporary art spaces, Kevin Bruk Gallery. Since the opening of his first space in the Design District seven years ago, Kevin Bruk has exhibited the works of established contemporary artists like Peter Halley, Kenny Scharf, and Fabian Marcaccio alongside significant emerging ones such as Matthew Brannon, Blake Rayne, and Daniel Hesidence, earning him a reputation of having an “eye for painting”.

At thirty-eight, with surf board at hand, warm smile and a no-nonsense attitude, Kevin Bruk and his “partner in crime” gallery Director, Adriana Vergara maintain the gallery’s position as a vital link to the global art world by approaching it as a dynamic duo on their own terms.

Kevin Bruk Gallery presented the first solo exhibition in Miami for English painter Richard Butler and Japanese Sculpture/Installation artist Midori Harima. Although different in form and format, the work of these artists brilliantly juxtaposes the conventional with the contemporary.

Employing traditional methods, oil paintings and paper sculptures, present-day themes of identity and human fragility are subliminally dealt with by both artists. In a neo-melancholic style Harima appropriates the delicacy of Japanese handmade paper and Butler the exaggerated proportions of Mannerist painting to mask the real, the somber.

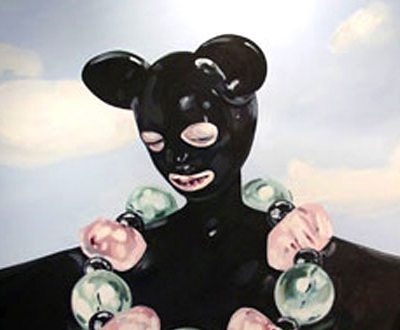

As we enter the gallery space, Richard Butler’s large scale, framed, nearly monochromatic, bust portraiture oil paintings of family and friends, portray more than just the subjects’ personalities. In a way, they seem to evoke Butler’s need to re-evaluate his own identity from an isolated stance. His subjects, a boy wrapped in black feathers, a figure in a leather “mouse” costume, a Geisha looking out into the horizon and a portrait of a scarred Marla Hanson are both beautifully painted and disturbing. Interestingly, all of the subjects seem to be absent, in a contemplative mode, except for Marla who stares at you in the eye, maybe Butler’s only “self portrait”?

Historically, portraiture served to idealize the sitters by presenting them alongside objects that stated or raised their stature. In contrast, Butler does not go out of his way to give his subjects a face lift. He presents them in a Gothic style, raw, exposing ghost-like expressions and “weather-worn” features. His symbols, the mask, the cross, the jeweled necklace, the fur, the eye patch and the bubble-like halo seem to derive from religious mysticism, and appear in their fetish style, more like protective talismans rather than status symbols.

The landscapes in which these characters are placed recall the subliminal paintings of German Romantic artist Caspar David Friederich (1774-1840). More psychological than actual, they represent a state of mind and serve as a backdrop to the characters’ seemingly peaceful presence. In reality, they are reflective of the geography, and light of the artist’s surroundings in upstate New York. Undoubtedly, his portraits reflect his desire to connect with the human spirit by creating a dialogue and connecting with the alter-ego of the “other”.

Ephemeral “papier mache” sculptures made out of Xeroxed images taken from various publications inhabit the latter part of the gallery space. Reacting against the seemingly loss of identity created by oversaturated consumerism and foreign influence in contemporary Japan, Midori Harima attempts to re-capture and re-create a dialogue with her fragile ancient culture.

{mospagebreak}

In her installations, she presents subtle melancholic vignettes of minimal proportion inviting the viewer to question the loss of identity created by globalization. In one room, we find an individually framed fox, serpent, and an owl confronted by a naked figure of a young girl who appears sad and immobilized by her current condition, maybe not understanding the icons of her past. In the corridor we find, “Leaping Fawn”, three spotted weightless dear hang delicately from the gallery ceiling by a fishing line.

The sculptures, shallow shells assembled by collages of black and white Xeroxes are adhered to construct the outer layers of the figures. Interestingly, her technique works as a metaphor to describe the existing status quo in Japanese culture where the Western mantle of influence has engulfed, it leaving it “skin deep”.

Deliberately, the animals or “magical creatures” she chooses to comment on the diminishing of her culture are taken from the iconography used in Shinto, the ancient native religion of Japan. In traditional Shinto Shrines, the fox, the Tengu (envisioned as a bird-like entity) and the Serpent, collectively known as Henge or shape-shifters, are used to cast off evil spirits.

Occupying the last room in the gallery is an installation reconstructing an idyllic landscape. A life-size sacred Sika deer, motionlessly confronts the viewer from behind an artificial curtain of rain. They face each other silently accepting the unavoidable, there’s no turning back. Unlike Sue-en Wong (recently showing at Bruk’s), who in her paintings employs imagery which seemingly celebrates the appropriation of Western culture in contemporary China, Midori once again makes reference to “paradise lost” and her longing to connect with nature.

In a globalized, politically charged environment where mass media drives perceptions and pushes the threshold for empathy, and tenderness, we find artists like Butler and Harima reaching to human landscapes and ancient cultures for a sense of identity and civilization.

By Mariangela Capuzzo

Be the first to comment