Charest-Weinberg’s art gallery occupies a space in the unassuming Wynwood Lofts complex on NW 23rd street. It’s called the building home since 2008. Unlike other galleries in the area, it doesn’t readily announce itself by occupying a ground floor space or brandishing its name in big block letters. Instead, it nearly sequesters itself in a two-loft space on the fourth floor, an attribute owner Eric Charest-Weinberg is proud of. “I wanted to create an environment that was a little bit challenging to get to, that was kind of removed from what everyone else was doing so I could focus on my goals and ambitions.”

Charest-Weinberg’s art gallery occupies a space in the unassuming Wynwood Lofts complex on NW 23rd street. It’s called the building home since 2008. Unlike other galleries in the area, it doesn’t readily announce itself by occupying a ground floor space or brandishing its name in big block letters. Instead, it nearly sequesters itself in a two-loft space on the fourth floor, an attribute owner Eric Charest-Weinberg is proud of. “I wanted to create an environment that was a little bit challenging to get to, that was kind of removed from what everyone else was doing so I could focus on my goals and ambitions.”

In doing so, he offers a unique space to exhibit and view contemporary artwork. Each of the two combined loft spaces has its own feel and contributes something different to the gallery as a whole. On one side, a clean white-walled exhibition space akin to many other contemporary galleries. On the other, a fabric-laced lounge that includes Charest-Weinberg’s office space and invites artists and guests to relax and discuss the work around them. “I was always attracted to the idea of creating a unique environment for viewing work, but also for having an ongoing dialogue with artists and people passionate about the arts in general.”

Charest-Weinberg’s own passion for the arts came at an early age. “I grew up in a very art-oriented house,” he says. His father was involved in the arts and both of his parents were avid collectors, focusing mainly on Canadian artists. At 15, his first job was in a gallery in Montreal’s Old Port District, where he mopped the floors, performed some clerical work and busied himself with framing duties. Brian Brisson, the gallery’s owner, became his mentor and helped Charest-Weinberg conceptualize his ideas of one day stepping up to fill the role of art dealer.

It was during his time as a fine arts student in New Brunswick that Charest-Weinberg fully decided to alter his course from an attempt to become a professional artist to exhibiting and promoting the artwork and artists he most strongly found a connection with. “I had an appreciation for what it meant to own a gallery and be involved with artists, and to create exhibitions in this space,” he says. “I worked with Brian closely, putting on various exhibitions outside of his space, and began socializing more with people that I had met along the way that were involved in the art world and could bring a very unique and important perspective.”

Through these conversations and interactions, Charest-Weinberg’s sensibilities and aesthetic tastes began to evolve. Where he once focused on the decorative and commercial arts, thanks to the work shown at Brisson’s gallery, he began to uncover the allure in more intense works by contemporary artists. “I found myself to be very comfortable with contemporary art. It was and is the cutting-edge movement of the art world.” Not long after, he gathered a group of Montreal artists and decided to open a unique experimental exhibition space.

After a second trip to Key West, Charest-Weinberg realized the island community was the perfect place for such an undertaking. A charming building on the upper end of Duval Street, boasting vaulted ceilings, Dade Country Pine, and just the right amount of dilapidation became the site of a restoration project that would result not only in a new art space, but also in an architectural restoration award.

“I brought Montreal artists down to Key West and put on exhibitions for about three years,” he says. “One of the reasons I really enjoyed Key West is because there was a vast population of people who had second and third homes on the island who were coming from all over the world. There was a culture being imported for a short amount of time there, and then it would leave.”

The success experienced in Key West, particularly with this group of people Charest-Weinberg was so taken with, enabled him to manufacture an international audience for the artists he represented. This global network of collectors and supporters aligned itself well with his overall goals, which had been on an international scale for some time. Place and its relationship with contemporary art would only grow more important to him as time went on.

After Hurricanes Wilma and Katrina hit the island, the gallery began to fare about as well as its surroundings. “The local government really mismanaged the PR after the fact and, in my opinion, really set Key West back,” Charest-Weinberg states. “I wanted to start looking for my next project, my next endeavor. I knew Key West wasn’t going to last forever. The most logical option was to move to Miami.”

That move, in 2008, placed Charest-Weinberg in the middle of Wynwood at a point in his life where his focus was to evolve his aesthetic tastes on a practical level. He redefined the types of artists he desired to work with and made changes to his roster to suit the new art that he became attracted to.

“Moving to Miami, I wanted to create something different and new for me; something that would take a lot of work and help me consistently learn,” he says. “Miami was a great option because I was particularly fond of the art fairs that were happening here. There was a real excitement in my mind being able to establish a space in Miami that could cater to what appeared to be the needs of people who were coming to visit the city and also the local collectors.”

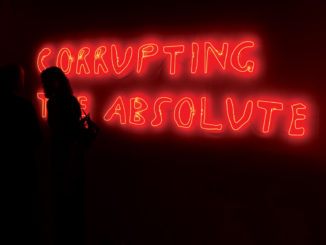

This at times emotional restructuring of his desires, tastes, and roster of artists culminated in what the Charest-Weinberg is today: an exhibition space that prides itself in focusing on artists and artwork that push the boundaries of contemporary art, striking new chords with collectors and art supporters, and generally staking new ground in the artistic community. In his effort to focus on the exhibition of an artist, rather than sales, Charest-Weinberg makes sure his exhibitions run a minimum of two months, with some going on much longer.

“It’s less about the idea of selling the work and more to create an environment that was designed for artistic expression,” he says. “It demonstrates a commitment to the work and also my desire to have the work exist in a context desired by the artists and myself.” Charest-Weinberg supports artists that include Tim Maxwell, whose “Tabula Rosa” exhibition was on view through the fall, and Fernando Mastrangelo, whose work was on display until February 29th.

Be the first to comment