While out walking a Second Saturday last March on NW 2nd Avenue in the middle of the street, I could see Marilyn Minter’s crazy-beautiful video on the back wall of David Castillo’s gallery. Bright red lips were licking, kissing, and slurping out green, gelatin-like stuff onto a glass behind which the video camera had captured all this lusciously bizarre movement and color. “Wow!”, I thought, “video when done well can hit you right in the head and gut, stopping you in your tracks!”

While out walking a Second Saturday last March on NW 2nd Avenue in the middle of the street, I could see Marilyn Minter’s crazy-beautiful video on the back wall of David Castillo’s gallery. Bright red lips were licking, kissing, and slurping out green, gelatin-like stuff onto a glass behind which the video camera had captured all this lusciously bizarre movement and color. “Wow!”, I thought, “video when done well can hit you right in the head and gut, stopping you in your tracks!”

Video art is undoubtedly the ultimate, ultra-contemporary art form. Unlike painting, sculpture, drawing, even installation, the very mechanism to make this genre did not exist a mere century ago, and really only entered the artistic arena in the 1960s. Since then, video has morphed, grown, and developed into a complex form all its own. Some video art remains distinctly narrative and film-like, while other’s focus is firmly grounded in performance-art roots. More recently, video has been graphed onto installation and sculpture, with projections kinetically molding the static form (think Tony Oursler).

Video, in other words, is an integral part of art today, and yet it remains somewhat elusive, particularly in Miami.

By elusive, I mean that there is not a large sub-set of people who are known as video artists here, or who are known mostly for their video output. Nor are there many gallery-shows dedicated exclusively to video. There are often video elements to certain shows, and many artists work with the medium, but it sometimes seems strange, in such a new art town, with its contemporary aesthetics and even its “Miami Vice” heritage, that video has not been a bigger player here. After that general impression, however, it is worth looking at what has been happening in the world of video in Miami’s relatively short lifetime, and whether that generalization is true.

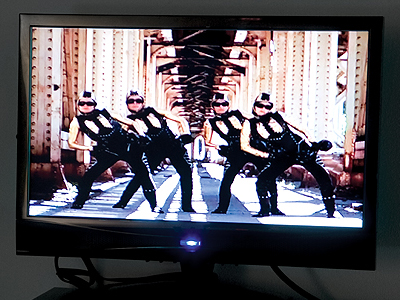

Back to the show at Castillo titled “Chained to a Creature of a Different Kingdom,” with the Minter piece, Green Pink Caviar, jumping off the wall, it was curated by former Miamian and now Los Angeles-based artist Annie Wharton, who works often with video. The show included 15 video works; some projected, some on TV screens, all thematically relating to bodily movements. Visitors might not have realized that this was one of the few, entirely video group shows (museums have had such exhibits, but a bit more on that later) presented here.

It is not that Miami is a stranger to film and video shows, but these are usually solo. The amount of video work in this show made it noteworthy, and made it possible to glimpse thematic trends. “From humorous to political to surreal to physical, the artists in the show run the gamut of works being made in the genre of action-based video art today,” according to Wharton.

All but one artist was based elsewhere, mainly New York and Los Angeles, traditionally the two hubs of video art making, so the scope was not provincial.

It also made me wonder, are people in L.A., for instance, seeing stuff that we aren’t? The answer, most likely, is yes and no. Does it matter that such major players as John Baldessari, Chris Burden and Bruce Nauman have been guiding lights in that city? Obviously yes, but it is never really fair or helpful to compare Miami to more historically developed and larger art centers. So what does Miami see?

In terms of local production, what we have seen is how multi-disciplinary video art really is. For example, the only Miami video in “Chained”, that came from Susan Lee-Chun, was a faux aerobic exercise tape, and was actually just one complementary element to a larger performance and installation piece she had done during last year’s Art Basel.

It is a good illustration of how video has taken an increasingly prominent role in art works, but not necessarily the starring one. In other words, one would not really call Lee-Chun simply a video artist; she works in a variety of media. The same can be said about The TM Sisters, who say they work with video, but also “Vjing, collage, clothing, installation, and ‘zines.” Or Jen Stark, who like the TM Sisters won a top award from the Museum of Contemporary Art’s video/film festival Optic Nerve, but few would label her a video artist.

It is becoming increasingly hard to pigeonhole artists. In fact MOCA’s Optic Nerve, the annual summer event since 1999, has played a large part in raising video’s profile in Miami, and a huge array of

Miami artists have participated throughout the years. Optic Nerve basically encourages artists, who have been working with any media, to experiment with the camera and see what they can come up with. The results have generally been as can be expected: some solid works, some bizarre ones, some bad ones, but that is what “experimental” is all about.

MOCA has also featured video in a number of high-profile shows, becoming an incubator of sorts of our video education (among many other exhibits, who can forget Isaac Julien’s “True North” back during Art Basel 2005?).

Non-commercial institutions here actually have a nice record of highlighting international video art. The now-defunct Moore Space showed some remarkable works during its run, and contributed to our fundamental knowledge of performance and video art. Other museums have introduced intriguing pieces, and shows that incorporated the genre as well. The best video retrospective to land on our shores came courtesy of the also defunct Miami Art Central, with its “Video: An Art, a History, 1965-2005.” In this sprawling, gorgeous show, Miamians might first have encountered works from the masters of the field, such as Bill Viola, Vito Acconci, Nauman, Oursler, and the pioneering Nam June Paik. In fact, a few art students at the time mentioned later that the show had been an inspiration for their own future work.

But back to the local: if you have looked for it, video has delivered some dramatic and quality moments all its own. There is an awful lot of bad video out there, but that is not unique to the genre; whether your instrument is a paintbrush or a camera, the talent originates behind the hand.

It would be hard to talk about local video without mentioning Clifton Childree. Although he uses installation to “frame” his work in some situations, Childree’s work is pure celluloid madness. His sepia-toned narratives are not performance art, nor are they looped images; they are funny, strange, quirky stories, quite different in fact from the generalized notion of conceptual video, which is why his work stands out from the crowd.

Another homeboy, Luis Gispert, also delves heavily into narrative video (or in this case we should really call it film). Although he is no longer based here, his work is liberally shown around town, and has been acclaimed for being a unique Miami vision.

Yet another former local, Natalia Benedetti, worked fairly exclusively with video in a more abstract way than the above two. She filmed water and reflections and light in an amazing exhibit at the MOCA Goldman Warehouse, which also featured a screen with a continual loop of free falling, skydiving bodies.

This is just to name a few. Video commands an increasing presence in individual shows, be it created locally or internationally. In other words, Miami’s video scene likely reflects a national one, even without our own Baldessaris.

In April, Gallery Diet in Wynwood hosted “Batty Cave,” a solo video and sculpture show from young local artist, Christy Gast. The main attraction was a 12-minute video narrative (as opposed to an Oursler or Peter Sarkisian “piece”), highlighting again that today video can come in different shapes, forms, and expressions. “I wouldn’t necessarily say that Miami artists just dabble in video,” says Diet’s director Nina Johnson, “but rather that its strong ties to performance-based work, and multi-media installations, make it a natural step for a lot of artists working here – or really anywhere – who are involved in the current dialogue.” In sum, she concludes: “I think that any contemporary art scene includes video, and Miami is no exception to this.”

In other words, it is hard to confine video to a provincial or physical locale – its very nature is portable and reproducible. Video artist and “Chained” curator Annie Wharton says, “I think my attraction stems from the combination of the two elements of painting and media-based explorations. Video, while highly technical, is also really so abstract and boundary-less; it’s compelling to discover form where it might not otherwise exist.”

Be the first to comment